Razing the Dead

Lowcountry develolpers disturb slave graves and lock out family members

BY JOHN VERNELSON

|

Although Middleton is relatively healthy and surrounded by people who

love and care for her, something is missing from her life: she has been

barred from visiting the graves of her father, a husband, and a son for

almost a half-century. The Old Alston Cemetery where they are buried was

closed to her and other African-American families in the mid-1950s by the

property owners.

Although Middleton is relatively healthy and surrounded by people who

love and care for her, something is missing from her life: she has been

barred from visiting the graves of her father, a husband, and a son for

almost a half-century. The Old Alston Cemetery where they are buried was

closed to her and other African-American families in the mid-1950s by the

property owners.

Old Alston Cemetery is off Parkers Ferry Road near Jacksonboro, about

25 miles south of Charleston. The graveyard is several hundred yards off

Parkers Ferry, concealed by woods and dense undergrowth. A locked metal

gate and a fence surround the property.

Old Alston Cemetery is off Parkers Ferry Road near Jacksonboro, about

25 miles south of Charleston. The graveyard is several hundred yards off

Parkers Ferry, concealed by woods and dense undergrowth. A locked metal

gate and a fence surround the property.

Middleton's home is less than five miles away but it might as well be

500, say her granddaughters, who remember visiting the cemetery as little

girls.

Middleton's home is less than five miles away but it might as well be

500, say her granddaughters, who remember visiting the cemetery as little

girls.

"We moved in with our grandmother when I was about nine years old,"

said Grant. "When [Middleton] sent us out to gather firewood, we always

seemed to end up at the cemetery. But now there are too many woods and

fences and gates in the way. I hope my grandmother gets to visit Old

Alston before she dies."

"We moved in with our grandmother when I was about nine years old,"

said Grant. "When [Middleton] sent us out to gather firewood, we always

seemed to end up at the cemetery. But now there are too many woods and

fences and gates in the way. I hope my grandmother gets to visit Old

Alston before she dies."

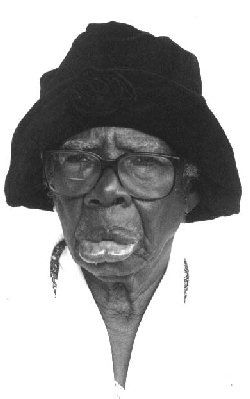

Sarah Middleton has been unable to visit the graves of several family members since the 1950s. |

King Cemetery, which dates to the 1850s, is about a half-mile off

Highway 17S on property known locally as Encampment Plantation just north

of Parkers Ferry Road.

King Cemetery, which dates to the 1850s, is about a half-mile off

Highway 17S on property known locally as Encampment Plantation just north

of Parkers Ferry Road.

Middleton said many of her friends and acquaintances are buried at

King Cemetery, and she remembers walking in funeral processions to the

graveyard on "the Old Road," a tree-lined lane that still runs from what

is now known as Highway 17S to the cemetery.

Middleton said many of her friends and acquaintances are buried at

King Cemetery, and she remembers walking in funeral processions to the

graveyard on "the Old Road," a tree-lined lane that still runs from what

is now known as Highway 17S to the cemetery.

In those days, Middleton said "the body was laid out" in the home for

bathing and dressing and other burial preparations. Coffins were built at

or near the home of the deceased and then loaded onto horse-drawn wagons.

Middleton remembers following "death wagons" in many funeral processions

along the Old Road to King Cemetery.

In those days, Middleton said "the body was laid out" in the home for

bathing and dressing and other burial preparations. Coffins were built at

or near the home of the deceased and then loaded onto horse-drawn wagons.

Middleton remembers following "death wagons" in many funeral processions

along the Old Road to King Cemetery.

"We dressed in black and sang hymns," she said. "If the funeral was

late, some of us carried torches. It was a long time ago, but I still

remember it."

"We dressed in black and sang hymns," she said. "If the funeral was

late, some of us carried torches. It was a long time ago, but I still

remember it."

Sanders and Grant said their grandmother wants to visit King Cemetery,

and hopes that Old Alston will someday be opened to her.

Sanders and Grant said their grandmother wants to visit King Cemetery,

and hopes that Old Alston will someday be opened to her.

"In those days," Grant said, "the people who owned the land set aside

certain areas for blacks to bury, and then after generations

"In those days," Grant said, "the people who owned the land set aside

certain areas for blacks to bury, and then after generations

King Cemetery wasn't rediscovered or reopened by accident. It first

came to attention about a year ago in a dispute between Charleston County

and the owners of land adjacent to the proposed site for a county dirt

mine. The county said it needed the dirt for road work in that part of the

county.

King Cemetery wasn't rediscovered or reopened by accident. It first

came to attention about a year ago in a dispute between Charleston County

and the owners of land adjacent to the proposed site for a county dirt

mine. The county said it needed the dirt for road work in that part of the

county.

Russ and Lee Pye, owners of the adjacent land, said the thousands of

gallons of water that would be pumped hourly from the 40-foot-deep,

20-acre pit would destroy the cemetery. The proposed mine site is part of

the 750-acre Sheppard Tract, land the county bought for $1.5 million in

1991 to use as a burial ground for ash produced by the county's waste

incinerator. The Sheppard Tract is part of what was once known as

Encampment Plantation. The mine site borders the Pye property and is about

200 feet from King Cemetery, which is on land owned by Westvaco

Corporation.

Russ and Lee Pye, owners of the adjacent land, said the thousands of

gallons of water that would be pumped hourly from the 40-foot-deep,

20-acre pit would destroy the cemetery. The proposed mine site is part of

the 750-acre Sheppard Tract, land the county bought for $1.5 million in

1991 to use as a burial ground for ash produced by the county's waste

incinerator. The Sheppard Tract is part of what was once known as

Encampment Plantation. The mine site borders the Pye property and is about

200 feet from King Cemetery, which is on land owned by Westvaco

Corporation.

Construction in the Lowcountry often means competing with archaeological and preservation interests. |

Meanwhile, Charleston County paid an Atlanta company $11,000 for an

archaeological survey of the cemetery in early February to determine its

boundaries and the number of graves therein. About 156 graves were

discovered, including four in a fire lane not previously believed to be

within the borders of the graveyard.

Meanwhile, Charleston County paid an Atlanta company $11,000 for an

archaeological survey of the cemetery in early February to determine its

boundaries and the number of graves therein. About 156 graves were

discovered, including four in a fire lane not previously believed to be

within the borders of the graveyard.

Dr. Michael Trinkley, executive director of the Chicora Foundation, a

Columbia-based nonprofit group dedicated to preserving the archaeological

and cultural resources of the Carolinas, found two other graves on land

that borders King Cemetery.

Dr. Michael Trinkley, executive director of the Chicora Foundation, a

Columbia-based nonprofit group dedicated to preserving the archaeological

and cultural resources of the Carolinas, found two other graves on land

that borders King Cemetery.

"It looks as if King Cemetery might be much larger than previously

believed," Trinkley said at the site shortly after the county's

archaeological survey was completed. "I probed only for 15 minutes or so

and located the two graves on the Pyes' land."

"It looks as if King Cemetery might be much larger than previously

believed," Trinkley said at the site shortly after the county's

archaeological survey was completed. "I probed only for 15 minutes or so

and located the two graves on the Pyes' land."

Trinkley, the Pyes and others who viewed the cemetery after the survey

said they were shocked at the way equipment operators scraped the boundary

around the cemetery. One witness said bulldozers were used, but the county

said the work was done with a backhoe.

Trinkley, the Pyes and others who viewed the cemetery after the survey

said they were shocked at the way equipment operators scraped the boundary

around the cemetery. One witness said bulldozers were used, but the county

said the work was done with a backhoe.

Trinkley, on the other hand, had no complaint. Deputy State

Archaeologist Dr. Jon Leader agreed, saying Garrow and Associates did "an

excellent job."

Trinkley, on the other hand, had no complaint. Deputy State

Archaeologist Dr. Jon Leader agreed, saying Garrow and Associates did "an

excellent job."

But the dispute between the Pyes and the county is about more than the

dirt mine and its effect on King Cemetery. There are other

"archaeologically sensitive" areas near the juncture where land owned by

the Pyes, Westvaco and Charleston County come together, including a

Revolutionary War encampment; the site of the Stono Slave Rebellion of

1739; and the home of Robert Young Hayne, elected governor of South

Carolina in 1832.

But the dispute between the Pyes and the county is about more than the

dirt mine and its effect on King Cemetery. There are other

"archaeologically sensitive" areas near the juncture where land owned by

the Pyes, Westvaco and Charleston County come together, including a

Revolutionary War encampment; the site of the Stono Slave Rebellion of

1739; and the home of Robert Young Hayne, elected governor of South

Carolina in 1832.

The dispute over the cemetery and the dirt mine has drawn the interest

of Duke University professor Peter H. Wood, author of a prize-winning

book, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 to

the Stono Rebellion. Wood said, "The field where the insurrection was

quelled lay near Jacksonboro, as is clear in contemporary accounts, and

apparently that site was on the ground now under dispute."

The dispute over the cemetery and the dirt mine has drawn the interest

of Duke University professor Peter H. Wood, author of a prize-winning

book, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 to

the Stono Rebellion. Wood said, "The field where the insurrection was

quelled lay near Jacksonboro, as is clear in contemporary accounts, and

apparently that site was on the ground now under dispute."

There are other "archaeologically sensitive" sites on the 750 acres

owned by the county, according to an archaeological survey conducted by

Garrow and Associates. On one site glass beads and burned bead fragments

were found that "may represent a ritualistic practice associated with a

slave burial," the survey said.

There are other "archaeologically sensitive" sites on the 750 acres

owned by the county, according to an archaeological survey conducted by

Garrow and Associates. On one site glass beads and burned bead fragments

were found that "may represent a ritualistic practice associated with a

slave burial," the survey said.

Other sites discovered in the survey include two "slave rows"

associated with Encampment Plantation; a late 19th early 20th century

domestic site with an unknown prehistoric component (Native American); and

artifacts from several other prehistoric and historic sites.

Other sites discovered in the survey include two "slave rows"

associated with Encampment Plantation; a late 19th early 20th century

domestic site with an unknown prehistoric component (Native American); and

artifacts from several other prehistoric and historic sites.

In the meantime, the Pyes offered to buy a 35-acre parcel of the

county's land that includes the dirt-mine site in late February, but the

county turned them down, saying the land is worth more than the

$1,000-an-acre offer. The county paid $2,000 an acre.

In the meantime, the Pyes offered to buy a 35-acre parcel of the

county's land that includes the dirt-mine site in late February, but the

county turned them down, saying the land is worth more than the

$1,000-an-acre offer. The county paid $2,000 an acre.

If the county had accepted their offer, the Pyes had intended to give

it to Oak Hall Plantation Inc., a nonprofit corporation whose purpose is

to preserve "archaeologically sensitive" land in the area. Oak Hall

Plantation was created by the Pyes.

If the county had accepted their offer, the Pyes had intended to give

it to Oak Hall Plantation Inc., a nonprofit corporation whose purpose is

to preserve "archaeologically sensitive" land in the area. Oak Hall

Plantation was created by the Pyes.

The land would also have been used as a buffer for King Cemetery, and

the Pyes promised in their offer-to-buy document to provide access to the

cemetery from Highway 17. Also included in land donations to Oak Hall

Plantation, but not included in the purchase offer, are four acres already

owned by the Pyes to be used for the cultivation of sweet grass, a type of

straw used for making baskets by Lowcountry artisans in the tradition of

their African ancestors.

The land would also have been used as a buffer for King Cemetery, and

the Pyes promised in their offer-to-buy document to provide access to the

cemetery from Highway 17. Also included in land donations to Oak Hall

Plantation, but not included in the purchase offer, are four acres already

owned by the Pyes to be used for the cultivation of sweet grass, a type of

straw used for making baskets by Lowcountry artisans in the tradition of

their African ancestors.

A week after refusing the Pyes' offer, Charleston County Council

withdrew its application for the permits needed to build the dirt mine. At

first blush that would appear to be a step in the right direction. But

Charleston County is not giving up on its plan to bury incinerator ash on

the Sheppard Tract.

A week after refusing the Pyes' offer, Charleston County Council

withdrew its application for the permits needed to build the dirt mine. At

first blush that would appear to be a step in the right direction. But

Charleston County is not giving up on its plan to bury incinerator ash on

the Sheppard Tract.

Nor is it going to revise its plans for the ash landfill complex in a

way that would allow it to jettison the need for the pit required for the

dirt mine.

Nor is it going to revise its plans for the ash landfill complex in a

way that would allow it to jettison the need for the pit required for the

dirt mine.

You can expect Charleston County Council to renew its permit

applications and try a little harder the second time around to meet the

permitting requirements of state law as well as one of its own ordinances

that prohibits development of historically and archaeologically

significant land.

You can expect Charleston County Council to renew its permit

applications and try a little harder the second time around to meet the

permitting requirements of state law as well as one of its own ordinances

that prohibits development of historically and archaeologically

significant land.