Trouble in Paradise

Workers demand decent pay on Hilton Head.

COMPILED FROM STAFF REPORTS

This year, while the business community prayed for sunny weather and

planned eagerly for a bigger payout than last year, another sentiment was

also gaining momentum. Island workers

This year, while the business community prayed for sunny weather and

planned eagerly for a bigger payout than last year, another sentiment was

also gaining momentum. Island workers

The antebellum theme of Hilton Head's beach resorts and the tightly

controlled labor force that maintains them make unlikely ingredients for

a workers' rights movement. But out of racial and economic division and a

long list of daily oppressions, the island's workers are telling a success

story. To understand, we have to take a step back in time.

The antebellum theme of Hilton Head's beach resorts and the tightly

controlled labor force that maintains them make unlikely ingredients for

a workers' rights movement. But out of racial and economic division and a

long list of daily oppressions, the island's workers are telling a success

story. To understand, we have to take a step back in time.

In 1865, Gen. William T. Sherman issued an order setting aside 400,000

acres of the sea islands south of Charleston to rent and later sell to

black families and loyal refugees. By that June, 40,000 black families had

settled on South Carolina's and Georgia's coastal regions.

In 1865, Gen. William T. Sherman issued an order setting aside 400,000

acres of the sea islands south of Charleston to rent and later sell to

black families and loyal refugees. By that June, 40,000 black families had

settled on South Carolina's and Georgia's coastal regions.

Over the last few decades, wealthy white entrepreneurs have taken

these lands back.

Over the last few decades, wealthy white entrepreneurs have taken

these lands back.

"Thirty years ago when they came in with the Hilton Head Inn, we built

it with our hands

"Thirty years ago when they came in with the Hilton Head Inn, we built

it with our hands

Wealthy retirees and vacationers have brought a higher cost of living,

higher land prices and higher property taxes to Hilton Head. Where hope

for a piece of the pie did not compel black families to sell their land,

taxes did. Today, most of the island's majority African-American work

force is bussed in from the rural counties surrounding Hilton Head, paying

at least an hour's wages and spending up to five hours a day on getting to

and from their jobs.

Wealthy retirees and vacationers have brought a higher cost of living,

higher land prices and higher property taxes to Hilton Head. Where hope

for a piece of the pie did not compel black families to sell their land,

taxes did. Today, most of the island's majority African-American work

force is bussed in from the rural counties surrounding Hilton Head, paying

at least an hour's wages and spending up to five hours a day on getting to

and from their jobs.

"You have to understand that for kids in high school in the outlying

counties their dream in life is to come work at one of the resorts, wear

a fancy uniform and earn $6 an hour," said one native islander. But the

plantation metaphor used by many of the island's resorts is not lost on

these workers. The bus drivers who bring 600 workers to the island daily

recently characterized the Lowcountry Regional Transit Authority for whom

they work a "slave farm."

"You have to understand that for kids in high school in the outlying

counties their dream in life is to come work at one of the resorts, wear

a fancy uniform and earn $6 an hour," said one native islander. But the

plantation metaphor used by many of the island's resorts is not lost on

these workers. The bus drivers who bring 600 workers to the island daily

recently characterized the Lowcountry Regional Transit Authority for whom

they work a "slave farm."

Opposition to these circumstances also has roots that go back many

years. In the late 1980s, Doris Grant, a fifth-generation resident of

Hilton Head, led a group called the Underground Railroad, which used

grassroots tactics to publicize the quasi-slave conditions in which blacks

on Hilton Head were still living.

Opposition to these circumstances also has roots that go back many

years. In the late 1980s, Doris Grant, a fifth-generation resident of

Hilton Head, led a group called the Underground Railroad, which used

grassroots tactics to publicize the quasi-slave conditions in which blacks

on Hilton Head were still living.

"My fight will never be over until we get a fair share," Grant said.

"Please remember Hilton Head Island is a resort island where we should be

making resort money, not slave wages. My grandmother always said, If they

ain't tired, I'm tired for them.'"

"My fight will never be over until we get a fair share," Grant said.

"Please remember Hilton Head Island is a resort island where we should be

making resort money, not slave wages. My grandmother always said, If they

ain't tired, I'm tired for them.'"

A core group of leaders grew up around Grant's Underground Railroad,

but found it hard to challenge the large hotels on the island. They got

some publicity in 1990 when "60 Minutes" did a story about the conditions

faced by island workers, including those on neighboring Daufuskie Island

where resort plantations threatened to destroy cemeteries where black

families had been buried for generations.

A core group of leaders grew up around Grant's Underground Railroad,

but found it hard to challenge the large hotels on the island. They got

some publicity in 1990 when "60 Minutes" did a story about the conditions

faced by island workers, including those on neighboring Daufuskie Island

where resort plantations threatened to destroy cemeteries where black

families had been buried for generations.

That same year, the Carolina Alliance for Fair Employment (CAFE), a

Greenville-based workers rights group, was expanding statewide. Arthur

Pinckney, a former shipyard worker at the Charleston Naval Yard and a

native islander from Mt. Pleasant, was hired to work part-time for CAFE.

That same year, the Carolina Alliance for Fair Employment (CAFE), a

Greenville-based workers rights group, was expanding statewide. Arthur

Pinckney, a former shipyard worker at the Charleston Naval Yard and a

native islander from Mt. Pleasant, was hired to work part-time for CAFE.

Pinckney heard about the stirrings on Hilton Head and went down to

investigate. As he recalls, there was immediate excitement about CAFE.

"There were overwhelming problems," he said, "and we were one of the first

groups that seemed truly willing to listen to people's job problems and

fight to improve their situation."

Pinckney heard about the stirrings on Hilton Head and went down to

investigate. As he recalls, there was immediate excitement about CAFE.

"There were overwhelming problems," he said, "and we were one of the first

groups that seemed truly willing to listen to people's job problems and

fight to improve their situation."

Grant liked the sound of CAFE, and thought it wouldn't be hard to get

a chapter going. And by March of 1991, a new chapter of CAFE, centered on

Hilton Head, was recognized and 25 members, led by Grant, began to meet.

Grant liked the sound of CAFE, and thought it wouldn't be hard to get

a chapter going. And by March of 1991, a new chapter of CAFE, centered on

Hilton Head, was recognized and 25 members, led by Grant, began to meet.

The issues they faced were numerous. The resorts were called

"plantations," which was offensive to many; there was no affordable

housing; many roads weren't paved in black neighborhoods; and workers

faced a range of illegal and abusive practices at the hands of employers.

The issues they faced were numerous. The resorts were called

"plantations," which was offensive to many; there was no affordable

housing; many roads weren't paved in black neighborhoods; and workers

faced a range of illegal and abusive practices at the hands of employers.

Three years of meetings and public job rights workshops brought CAFE

new members, a higher profile in the community, and even a meeting with

President-elect Clinton's transition team. Despite these efforts, problems

continued.

Three years of meetings and public job rights workshops brought CAFE

new members, a higher profile in the community, and even a meeting with

President-elect Clinton's transition team. Despite these efforts, problems

continued.

In 1994, an employee from the Melrose Resort on Daufuskie Island

contacted CAFE because of job problems he and others were having. He

became a CAFE member and expressed interest in unionizing. CAFE put the

employee in touch with the International Union of Operating Engineers

(IUOE).

In 1994, an employee from the Melrose Resort on Daufuskie Island

contacted CAFE because of job problems he and others were having. He

became a CAFE member and expressed interest in unionizing. CAFE put the

employee in touch with the International Union of Operating Engineers

(IUOE).

IUOE organizers from Charlotte, N.C., held a series of meetings with

Melrose employees, and a biracial group of over 30 employees formed an

organizing committee.

IUOE organizers from Charlotte, N.C., held a series of meetings with

Melrose employees, and a biracial group of over 30 employees formed an

organizing committee.

Over the course of the three-month campaign, CAFE and the IUOE

dev-eloped an innovative labor community alliance. Public interest and

support were rallied through community events. CAFE members began printing

a one-page newsletter written by local workers and highlighting the

problems at the Melrose Resort and at other hotels on the island.

Over the course of the three-month campaign, CAFE and the IUOE

dev-eloped an innovative labor community alliance. Public interest and

support were rallied through community events. CAFE members began printing

a one-page newsletter written by local workers and highlighting the

problems at the Melrose Resort and at other hotels on the island.

In the last days of the union drive, CAFE and IUOE brought national

attention to the campaign by distributing a letter to Melrose employees

from the Rev. Jesse Jackson. He wrote, "You are part of an important and

historic struggle for justice and respect at Melrose Resort. You have an

opportunity to build a strong union and to create a better life for

yourself, your family and your community."

In the last days of the union drive, CAFE and IUOE brought national

attention to the campaign by distributing a letter to Melrose employees

from the Rev. Jesse Jackson. He wrote, "You are part of an important and

historic struggle for justice and respect at Melrose Resort. You have an

opportunity to build a strong union and to create a better life for

yourself, your family and your community."

Many observers, including the law firm employed by the Melrose Resort

to steer the employees away from unionization, believe this letter was

crucial in solidifying the pro-union majority.

Many observers, including the law firm employed by the Melrose Resort

to steer the employees away from unionization, believe this letter was

crucial in solidifying the pro-union majority.

On Oct. 27, 1994, employees of the Melrose Resort made history, voting

98 to 45 to be represented by IUOE. Those workers became the first in the

Hilton Head area to successfully organize for union representation.

On Oct. 27, 1994, employees of the Melrose Resort made history, voting

98 to 45 to be represented by IUOE. Those workers became the first in the

Hilton Head area to successfully organize for union representation.

A year and a half later, monthly contract negotiations still have not

resulted in a contract agreement. But as the negotiations drag on, the

community-labor alliance grows stronger.

A year and a half later, monthly contract negotiations still have not

resulted in a contract agreement. But as the negotiations drag on, the

community-labor alliance grows stronger.

Last spring, dozens of organizers from across the South came to Hilton

Head to protest the contract delays at Melrose. They joined the

Ministerial Alliance, the NAACP, and the local Democratic club, who had

formed an unprecedented local coalition to support Melrose workers.

Last spring, dozens of organizers from across the South came to Hilton

Head to protest the contract delays at Melrose. They joined the

Ministerial Alliance, the NAACP, and the local Democratic club, who had

formed an unprecedented local coalition to support Melrose workers.

In February, CAFE members distributed 600 "wanted" fliers featuring

Melrose's General Manager Pierre Renault, and set up a 12-foot inflatable

rat named Mickey Melrose near the entrance to the plantation where Renault

lives.

In February, CAFE members distributed 600 "wanted" fliers featuring

Melrose's General Manager Pierre Renault, and set up a 12-foot inflatable

rat named Mickey Melrose near the entrance to the plantation where Renault

lives.

Meanwhile, the union filed dozens of unfair labor practice charges

with the National Labor Relations Board. Most of the charges

Meanwhile, the union filed dozens of unfair labor practice charges

with the National Labor Relations Board. Most of the charges

The community-labor alliance that arose to support Melrose workers

moved on to support other island workers:

The community-labor alliance that arose to support Melrose workers

moved on to support other island workers:

LRTA bus drivers have been denied wage increases for more than three

years, and remain at the bottom of the pay scale for transit drivers in

South Carolina. Their fight for better working conditions became a focus

of last month's week of actions.

LRTA bus drivers have been denied wage increases for more than three

years, and remain at the bottom of the pay scale for transit drivers in

South Carolina. Their fight for better working conditions became a focus

of last month's week of actions.

Years of anger and organizing generated the steam to propel the week

of actions during this year's MCI Heritage Golf Classic. Workers on Hilton

Head were joined by members from the Food and Allied Service Trade of the

AFL-CIO, the IUOE, CAFE, South Carolina United Action and from grassroots

groups in several states.

Years of anger and organizing generated the steam to propel the week

of actions during this year's MCI Heritage Golf Classic. Workers on Hilton

Head were joined by members from the Food and Allied Service Trade of the

AFL-CIO, the IUOE, CAFE, South Carolina United Action and from grassroots

groups in several states.

"We wanted to push forward negotiations at Melrose, win a concrete

victory for LRTA bus drivers, educate more workers about what their rights

are, and let the tourists know that their plantation vacation comes at

somebody else's expense," said Simon Greer of CAFE.

"We wanted to push forward negotiations at Melrose, win a concrete

victory for LRTA bus drivers, educate more workers about what their rights

are, and let the tourists know that their plantation vacation comes at

somebody else's expense," said Simon Greer of CAFE.

Protesters kicked off the week on April 16, passing out thousands of

flyers in hotels, restaurants, shopping malls and at traffic intersections

across Hilton Head. Some received the flyers with puzzled politeness while

others snarled and said things like, 'Get a real job." Or, "If the

workers don't like it, they can go get higher-paying jobs somewhere else."

Protesters kicked off the week on April 16, passing out thousands of

flyers in hotels, restaurants, shopping malls and at traffic intersections

across Hilton Head. Some received the flyers with puzzled politeness while

others snarled and said things like, 'Get a real job." Or, "If the

workers don't like it, they can go get higher-paying jobs somewhere else."

On Wednesday before dawn, LRTA bus drivers and Melrose employees were

greeted by supporters with donuts and flyers poking fun at the workers'

bosses.

On Wednesday before dawn, LRTA bus drivers and Melrose employees were

greeted by supporters with donuts and flyers poking fun at the workers'

bosses.

On Thursday morning, traffic coming onto the island was brought to a

crawl by a motorcade of vehicles traveling at low speed. When the traffic

did make it over the bridge, they were met by 15 protesters waving

American flags standing next to the now-famous giant inflatable rat

On Thursday morning, traffic coming onto the island was brought to a

crawl by a motorcade of vehicles traveling at low speed. When the traffic

did make it over the bridge, they were met by 15 protesters waving

American flags standing next to the now-famous giant inflatable rat

On Thursday evening, members of AFL-CIO and IUOE rode on workers'

buses to educate them about their job rights. These "union schools"

brought new requests from island workers for help with organizers'

efforts.

On Thursday evening, members of AFL-CIO and IUOE rode on workers'

buses to educate them about their job rights. These "union schools"

brought new requests from island workers for help with organizers'

efforts.

"Two years ago you couldn't find a union organizer down here, and this

week we had six of them riding on the buses talking with people," said

CAFE member Mary Heyward.

"Two years ago you couldn't find a union organizer down here, and this

week we had six of them riding on the buses talking with people," said

CAFE member Mary Heyward.

On Friday, LRTA bus drivers announced a major victory. Ten days

before, the drivers and CAFE held a press conference to announce five

demands, including a wage increase and the termination or resignation of

Sam Smith, their manager. On the 10th day, after a flyer displaying an

unflattering cartoon of Smith appeared on his desk, he took a permanent

leave from his job, following on the heels of LRTA board chairperson Ron

Voegeli, who resigned under pressure the day before.

On Friday, LRTA bus drivers announced a major victory. Ten days

before, the drivers and CAFE held a press conference to announce five

demands, including a wage increase and the termination or resignation of

Sam Smith, their manager. On the 10th day, after a flyer displaying an

unflattering cartoon of Smith appeared on his desk, he took a permanent

leave from his job, following on the heels of LRTA board chairperson Ron

Voegeli, who resigned under pressure the day before.

"This is a historic day for the bus drivers," Greer said. "The drivers

are heroes for all island workers. They have had the courage to stand up

and they've proven that together we can win."

"This is a historic day for the bus drivers," Greer said. "The drivers

are heroes for all island workers. They have had the courage to stand up

and they've proven that together we can win."

Attention was turned for the rest of the week on the contract fight

at the Melrose Resort. As Eric Coney, an employee of the resort and a

negotiating team member for the union, explained, "Management changed at

Melrose once a year. We lost our sense of family at Melrose along with

trust, benefits and wages. That's why we're fighting for this contract."

Attention was turned for the rest of the week on the contract fight

at the Melrose Resort. As Eric Coney, an employee of the resort and a

negotiating team member for the union, explained, "Management changed at

Melrose once a year. We lost our sense of family at Melrose along with

trust, benefits and wages. That's why we're fighting for this contract."

While past protests against Melrose took place on Hilton Head, on

Friday during the largest check-in day of the week, boats of protesters

went over to the resort itself. A protester from the Student Environmental

Action Coalition in Chapel Hill, N.C., said, "We caught them completely

off guard. We drove around the island in golf carts and slowed their

shuttle buses down. We leafleted them as they came off the boat and

chanted, Hey, hey, hey, how many slaves did you buy today?'"

While past protests against Melrose took place on Hilton Head, on

Friday during the largest check-in day of the week, boats of protesters

went over to the resort itself. A protester from the Student Environmental

Action Coalition in Chapel Hill, N.C., said, "We caught them completely

off guard. We drove around the island in golf carts and slowed their

shuttle buses down. We leafleted them as they came off the boat and

chanted, Hey, hey, hey, how many slaves did you buy today?'"

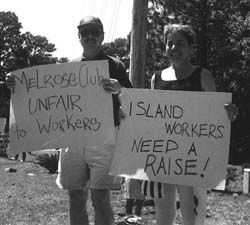

On Saturday, at the main traffic circle on Hilton Head, 30 protesters

carried signs saying "Take Your Plantation and Shove It," "Decent Pay for

Decent Work" and "Honk If You're Greedy."

On Saturday, at the main traffic circle on Hilton Head, 30 protesters

carried signs saying "Take Your Plantation and Shove It," "Decent Pay for

Decent Work" and "Honk If You're Greedy."

Meanwhile, at the Heritage golf tournament, a boat pulled in just off

shore from the 18th hole, where thousands were gathered in respectful

silence of the golfers. With a rented PA system, protesters blared social

justice songs and recorded testimony from Melrose workers.

Meanwhile, at the Heritage golf tournament, a boat pulled in just off

shore from the 18th hole, where thousands were gathered in respectful

silence of the golfers. With a rented PA system, protesters blared social

justice songs and recorded testimony from Melrose workers.

While the Coast Guard drove the boat away, protesters with passes

inside the golf tournament distributed thousands of cards asking visitors

to remember that after serving their food, cleaning their rooms, and

hauling their bags, that the workers too had families to go home and take

care of.

While the Coast Guard drove the boat away, protesters with passes

inside the golf tournament distributed thousands of cards asking visitors

to remember that after serving their food, cleaning their rooms, and

hauling their bags, that the workers too had families to go home and take

care of.

On the final day of actions, the wired-for-sound boat used the

previous day went to Daufuskie Island and serenaded Melrose Resort members

as they boarded a shuttle boat to go home. Stunned, the captive audience

listened as the PA system broadcast Jimmy Cliff singing "Get up, stand up.

Stand up for your rights." As if on cue, a group of African American

Melrose employees came down the boardwalk with their fists raised high in

the air.

On the final day of actions, the wired-for-sound boat used the

previous day went to Daufuskie Island and serenaded Melrose Resort members

as they boarded a shuttle boat to go home. Stunned, the captive audience

listened as the PA system broadcast Jimmy Cliff singing "Get up, stand up.

Stand up for your rights." As if on cue, a group of African American

Melrose employees came down the boardwalk with their fists raised high in

the air.

Back at Sea Pines Plantation, where the golf tournament was

concluding, three patrol boats stationed themselves to stop a repeat

performance at the 18th hole. The expected boat never came. Instead, a

plane appeared trailing a banner that read: "Melrose empoyees deserve a

fair contract now." For two hours, the plane circled overhead, leaving an

indelible memory for the thousands of golfers who had come to enjoy the

island pleasures made available to those with hefty paychecks and stock

portfolios.

Back at Sea Pines Plantation, where the golf tournament was

concluding, three patrol boats stationed themselves to stop a repeat

performance at the 18th hole. The expected boat never came. Instead, a

plane appeared trailing a banner that read: "Melrose empoyees deserve a

fair contract now." For two hours, the plane circled overhead, leaving an

indelible memory for the thousands of golfers who had come to enjoy the

island pleasures made available to those with hefty paychecks and stock

portfolios.

After a week of little sleep and much fellowship, protesters gathered

at a local church for a banquet and the chance to reflect on what they had

achieved. Powerful men had resigned, workers took risks and stood up for

themselves, and the blissful ease of plantation life was disrupted at

every turn.

After a week of little sleep and much fellowship, protesters gathered

at a local church for a banquet and the chance to reflect on what they had

achieved. Powerful men had resigned, workers took risks and stood up for

themselves, and the blissful ease of plantation life was disrupted at

every turn.

The strength the AFL-CIO and the IUOE brought to this year's protest

made it a particularly successful effort. While the week of actions didn't

achieve a total shut down, it was clear to workers, resort managers and

tourists alike that things will never be the same on Hilton Head.

The strength the AFL-CIO and the IUOE brought to this year's protest

made it a particularly successful effort. While the week of actions didn't

achieve a total shut down, it was clear to workers, resort managers and

tourists alike that things will never be the same on Hilton Head.

"My fight will never be over until we get a fair share. Please remember Hilton Head Island is a resort island where we should be making resort money, not slave wages."

Doris Grant