Spoleto

Behind the scenes

BY JOHN VERNELSON

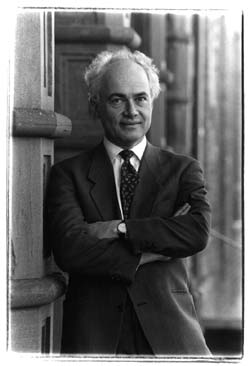

Nigel Redden |

"What he wanted to do was build a miniature house on the corner with

a Hugo tree lying across it, but I convinced him that was too negative,"

Alston said. "I told him we needed to do something more positive with this

corner in East Side Neighborhood because it's on America Street, and the

art should say something positive to the people who live here, not remind

them of Hurricane Hugo."

"What he wanted to do was build a miniature house on the corner with

a Hugo tree lying across it, but I convinced him that was too negative,"

Alston said. "I told him we needed to do something more positive with this

corner in East Side Neighborhood because it's on America Street, and the

art should say something positive to the people who live here, not remind

them of Hurricane Hugo."

The art the two men were to make on that corner went on to become what

many critics termed "the strongest piece" among a 61-exhibition visual

arts Spoleto project titled "Places with a Past: New Site-Specific Art in

Charleston."

The art the two men were to make on that corner went on to become what

many critics termed "the strongest piece" among a 61-exhibition visual

arts Spoleto project titled "Places with a Past: New Site-Specific Art in

Charleston."

Hammons was commissioned to create a large-scale assemblage of objects

gathered in Charleston that would explore the African-American experience.

Hammons was commissioned to create a large-scale assemblage of objects

gathered in Charleston that would explore the African-American experience.

Alston's idea was to build a 20-foot-long, door-wide, two-story single

house that would incorporate various styles of Charlestonian architecture.

The different styles, materials and construction methods would be labeled.

Inside would be drawings and paintings of objects appropriate to the

themes of the piece by local artist Larry Jackson.

Alston's idea was to build a 20-foot-long, door-wide, two-story single

house that would incorporate various styles of Charlestonian architecture.

The different styles, materials and construction methods would be labeled.

Inside would be drawings and paintings of objects appropriate to the

themes of the piece by local artist Larry Jackson.

On the corner opposite the miniature house would be a small park, the

centerpiece of which would be a black nationalist flag flying atop a

50-foot-tall flagpole. A billboard to the left of the flagpole would

depict the faces of black youth with eyes lifted toward the flag.

On the corner opposite the miniature house would be a small park, the

centerpiece of which would be a black nationalist flag flying atop a

50-foot-tall flagpole. A billboard to the left of the flagpole would

depict the faces of black youth with eyes lifted toward the flag.

The back wall of the miniature house would be emblazoned with the

words:

The back wall of the miniature house would be emblazoned with the

words:

"The Afro-American has become heir to the myths

that it is better to be poor than rich, lower class rather than middle or upper, easygoing rather than industrious, extravagant rather than thrifty, and athletic rather than academic."

"The Afro-American has become heir to the myths

that it is better to be poor than rich, lower class rather than middle or upper, easygoing rather than industrious, extravagant rather than thrifty, and athletic rather than academic."

Other works in the 1991 exhibition that mined the city landscape for

its rich repository of meanings

Other works in the 1991 exhibition that mined the city landscape for

its rich repository of meanings

Of the 61 pieces, only one remains, the miniature single-house and

park on America Street. Its existence is heavy with irony. "Places with a

Past," the brainchild of Nigel Redden, general manager of the 1991 Spoleto

Festival, was said by critics to be one of the most ambitious visual arts

projects ever undertaken, yet it gave Spoleto founder Gian Carlo Menotti

the excuse he wanted to force Redden out.

Of the 61 pieces, only one remains, the miniature single-house and

park on America Street. Its existence is heavy with irony. "Places with a

Past," the brainchild of Nigel Redden, general manager of the 1991 Spoleto

Festival, was said by critics to be one of the most ambitious visual arts

projects ever undertaken, yet it gave Spoleto founder Gian Carlo Menotti

the excuse he wanted to force Redden out.

At the time, Menotti called the exhibition "silly and sophomoric," and

said it was not fit for "a cheap discotheque." Menotti charged that Redden

was the leader of a challenge to his role as festival artistic director,

and told the Spoleto board he would resign unless Redden, festival board

chair Ross A. Markwardt and festival president Edgar F. Daniels quit.

At the time, Menotti called the exhibition "silly and sophomoric," and

said it was not fit for "a cheap discotheque." Menotti charged that Redden

was the leader of a challenge to his role as festival artistic director,

and told the Spoleto board he would resign unless Redden, festival board

chair Ross A. Markwardt and festival president Edgar F. Daniels quit.

All three eventually bowed out, leaving Menotti in charge. But less

than two years later, with Spoleto deep in debt, Menotti, in another fit

of temper, walked out on the festival, citing challenges to his artistic

vision as the reason.

All three eventually bowed out, leaving Menotti in charge. But less

than two years later, with Spoleto deep in debt, Menotti, in another fit

of temper, walked out on the festival, citing challenges to his artistic

vision as the reason.

Redden had been general manager of Spoleto for six years when Menotti

forced him out. He had managed the festival with a combination of artistic

vision and business acumen that kept it consistently in the black and

artistically ahead of its time.

Redden had been general manager of Spoleto for six years when Menotti

forced him out. He had managed the festival with a combination of artistic

vision and business acumen that kept it consistently in the black and

artistically ahead of its time.

"Nigel had the right idea with Places with a Past.'" Alston said

recently at the America Street corner. "Before that exhibition, Spoleto

hadn't done much to involve the black community. All Menotti seemed to

care about was the black-tie crowd, not black people who live in the city.

"Nigel had the right idea with Places with a Past.'" Alston said

recently at the America Street corner. "Before that exhibition, Spoleto

hadn't done much to involve the black community. All Menotti seemed to

care about was the black-tie crowd, not black people who live in the city.

"Look at this corner," Alston said. "The people here were affected by

the art in such a way that they keep this corner clean. You can come here

late at night and you'll be safe. This corner used to be notorious

"Look at this corner," Alston said. "The people here were affected by

the art in such a way that they keep this corner clean. You can come here

late at night and you'll be safe. This corner used to be notorious

The Alston/Hammons miniature single house made the cover of Art in

America, and was featured in many other national and international art

publications. Such publicity has drawn countless teachers, architects and

artists to the site in the years since, Alston said, providing him the

chance to travel "all over the world" to talk about historic renovation,

preservation and how art can affect culture.

The Alston/Hammons miniature single house made the cover of Art in

America, and was featured in many other national and international art

publications. Such publicity has drawn countless teachers, architects and

artists to the site in the years since, Alston said, providing him the

chance to travel "all over the world" to talk about historic renovation,

preservation and how art can affect culture.

"When I talk about this corner to students and others who come, I

mention the festival," he said, "but most people associated with the

festival don't realize what this corner has meant to Spoleto since 1991.

And they sure as hell don't realize what a difference it has made in East

Side."

"When I talk about this corner to students and others who come, I

mention the festival," he said, "but most people associated with the

festival don't realize what this corner has meant to Spoleto since 1991.

And they sure as hell don't realize what a difference it has made in East

Side."

Alston is in the process of refurbishing the single-house for a summer

program for East Side kids that has been in place since 1991. Participants

learn about art, history, construction and their culture.

Alston is in the process of refurbishing the single-house for a summer

program for East Side kids that has been in place since 1991. Participants

learn about art, history, construction and their culture.

Alston will also re-erect the billboard depicting black kids looking

at the black nationalist flag. The refurbishing coincides with Redden's

return last October as general manager of Spoleto. As general manager,

Redden is responsible for fund-raising, administration, marketing, union

negotiations, artist contracts, board development and programming.

Alston will also re-erect the billboard depicting black kids looking

at the black nationalist flag. The refurbishing coincides with Redden's

return last October as general manager of Spoleto. As general manager,

Redden is responsible for fund-raising, administration, marketing, union

negotiations, artist contracts, board development and programming.

Just as Alston keeps the America Street corner alive with an art

project made possible by Redden's idea, Redden is breathing new financial

and artistic life into Spoleto.

Just as Alston keeps the America Street corner alive with an art

project made possible by Redden's idea, Redden is breathing new financial

and artistic life into Spoleto.

Since his return, the festival has raised $1.6 million in special

funds to erase $1.5 million in losses from the 1994 festival, cutting by

more than half an accumulated debt of $3 million.

Since his return, the festival has raised $1.6 million in special

funds to erase $1.5 million in losses from the 1994 festival, cutting by

more than half an accumulated debt of $3 million.

During the same period, the Charleston festival has reduced its

outstanding bills to $80,312 from $1,130,980 and has moved ahead of

schedule on fundraising for this year's event.

During the same period, the Charleston festival has reduced its

outstanding bills to $80,312 from $1,130,980 and has moved ahead of

schedule on fundraising for this year's event.

In addition to helping ensure the long-term financial health of the

festival, Redden committed this year's festival to producing the American

premiers of Janacek's "The Excursions of Mr. Broucek," Philip Glass' "Les

Enfants Terribles" and the world premiere of Lee Breuer's "Peter and

Wendy." These are among the 114 performances of 45 programs the festival

will present from May 24 through June 9.

In addition to helping ensure the long-term financial health of the

festival, Redden committed this year's festival to producing the American

premiers of Janacek's "The Excursions of Mr. Broucek," Philip Glass' "Les

Enfants Terribles" and the world premiere of Lee Breuer's "Peter and

Wendy." These are among the 114 performances of 45 programs the festival

will present from May 24 through June 9.

"It's easy to raise money if you have a good idea to sell," Redden

said in a recent interview. "The art comes first, of course, but if you

put something on stage that's wonderful, excites the audience and involves

them in the dialogue with performers and the festival [board], it works

artistically and economically

"It's easy to raise money if you have a good idea to sell," Redden

said in a recent interview. "The art comes first, of course, but if you

put something on stage that's wonderful, excites the audience and involves

them in the dialogue with performers and the festival [board], it works

artistically and economically

"I'm 45 now," said Redden, a Yale graduate with a B.A. in Art History.

"I began at 18 with the festival in Italy. I've done everything there is

to do at the festival except perform.

"I'm 45 now," said Redden, a Yale graduate with a B.A. in Art History.

"I began at 18 with the festival in Italy. I've done everything there is

to do at the festival except perform.

"To make it all work, you have to keep up with production details and

the budget, line item by line item. But first and foremost you have to

love art

"To make it all work, you have to keep up with production details and

the budget, line item by line item. But first and foremost you have to

love art

Festival Manager Nigel Redden