Who's Driving DHEC?

BY BRETT BURSEY

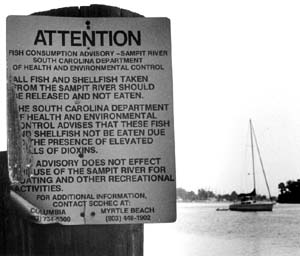

It isn't this state's "smiling faces and beautiful places" that attracted hazardous waste incinerators, toxic landfills and the country's largest radioactive dump to South Carolina. It is this state's weak environmental laws that draw polluting industries here. It is also why South Carolina has more toxic waste sites on the federal Super Fund list, per capita, than any other state.

To understand how we got where we are, you have to understand who is calling the shots.

DHEC is driven by a seven-member board which is appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Senate. Six members represent the congressional districts; the at-large member serves as the board's chairperson.

Other than per diem expenses, board members are not paid a salary.

In keeping with the agency's mandate to promote industry, most of the board members over the years have had business or industrial backgrounds rather than environmental expertise.

Since the board nominees are selected without a merit review and with no regard for experience or training in public health or environmental matters, the seats are likely to be filled by supporters of the governor.

All of the members serving on the current board are Republicans who were appointed or reappointed to four-year terms by Gov. David Beasley.

The governor's most controversial appointment was that of Cindi Mosteller in District 1. Mosteller runs a Charleston real estate firm and holds a master's degree in biblical studies. She founded the local chapter of the national Right to Life organization in 1988, and has taken part in anti-choice demonstrations at women's clinics.

In 1992, Mosteller served as "creator/chairman" of the "Parents against Clinton Campaign," holding press conferences in 10 cities across the country to denounce the president's family values. Mosteller also served as cochair of the Charleston County Beasley for Governor Campaign.

Mosteller's father is George Campsen Jr., a wealthy Charleston developer.

During confirmation hearings, Mosteller admitted that she didn't understand the term "nonpoint source pollution," or runoff, the biggest polluter of surface water.

Beasley's other appointments include:

District 2 — Brian K. Smith is a 36-year-old car dealer with a BA in education. He is president of two businesses that are licensed by DHEC, as well as president of Custom Builders.

District 3 — Rodney Grandy Jr., originally appointed by Gov. Carroll Campbell, Grandy retired in Aiken after working for 30 years as a top-level Exxon executive. Grandy stepped down in the early '90s as president of Exxon Chemical Europe, and is currently the owner of American Size & Chemical Company.

District 4 — Richard E. Jabbour, another Campbell appointee, is a Spartanburg dentist. Most notable for his opposition to confidential AIDS testing, Jabbour surprised environmentalists recently by going against a staff decision to permit a marina on John's Island. The board refused to permit the man-made waterway the marina required.

District 5 — William Martin Hull Jr. is a Rock Hill ophthalmologist. Hull has given observers the distinct impression that he believes environmentalists are merely obstacles to be overcome.

District 6 — Roger Leaks Jr. is the only African-American on the board. A Campbell holdover, Leaks is a Republican activist as well as a colonel in the Army Reserve. He has served on the State Election Commission and on the Central Midlands Regional Planning Council.

"I did not know that (supporting industrial development) was part of our mission," Leaks said in a recent interview. "I was told that our mission is to protect the health and environment of the state. If we can do the two together, I don't see anything wrong with it, but there are times when it is impossible."

At Large — John Hay Burriss serves as DHEC's chairperson. A Republican legislator from 1984 through 1988, Burriss followed in the footsteps of his father, Moffatt Burriss, founder and executive director of the South Carolina Policy Council, a conservative think tank and lobby.

The Burriss family owns multimillion-dollar construction and development firms. One of Burriss' business deals has drawn fire recently. Burriss is an owner in Bull Point Limited Development Corp., which is building Bull Point Plantation in Beaufort County. Burriss and associates sought and obtained a DHEC permit for 150 septic tanks.

Local landowners organized and appealed the permit. While DHEC continues to issue septic permits at Bull Point, nine at last count, the citizens' group has appealed every permit.

"DHEC gave their approval for the entire development without notice or public hearings," said Jimmy Chandler, the group's attorney. "We are going to appeal as far as we have to."

Chandler said, "There is a flaw in DHEC's system" that benefits developers.

The citizens' group feels out gunned in its effort to stop Burriss from getting septic permits; Burriss refused comment on the matter.

The only two Campbell appointees not reconfirmed by Beasley voted in favor of requiring a cash bond for the eventual cleanup of the Laidlaw toxic dump in Sumter County.

Sandra Molander, the former District 2 board member who voted for a Laidlaw cash bond, said, "The governor announced he was getting rid of me in February, and my term wasn't over until June. I'm a Republican, but not a good Beasley Republican."

In contrast to DHEC, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Health and Natural Resources is governed by a 17-member board (13 appointed by the governor and four by the legislature) that oversees air and water quality permits.

Dan Besse, who serves on North Carolina's DEHNR's Environmental Management Commission — the equivalent of the DHEC board — said, "Our commission is chosen from a variety of expertises. We have slots for a medical doctor, industrial water specialist, local government, air quality, business interests and others."

Mary Kelly, a longtime environmental activist with the League of Women Voters, probably holds the record for attending DHEC board meetings. "Given the scope of the work and the breadth of knowledge needed," Kelly said, "the size and qualifications of the board are inadequate."

Kelly suggests that the DHEC board have "people of different backgrounds and expertise. Because the board can overturn decisions by administrative law judges, it would be good to have a lawyer on the board.

"The board also makes important decisions regarding hospitals and nursing homes," she said. "They determine if new hospitals or expansions are needed, and check off on certain big-ticket items. In the past, this is where a lot of political pressure has been brought to bear. It all comes down to big money."

Board member Leaks said, "I don't necessarily think we need [qualifications], because we act like a jury. We hear testimony and make decisions. We have to rely on staff expertise to do what is in the best interest of the state."

As for recent cases where the board overturned decisions made by its own staff, and in some cases the administrative law judge, Leaks said, "Well, sometimes there are other considerations."

Since DHEC board nominees are selected without a merit review and without regard for experience or training in health and environmental matters, the seats are likely to be filled by supporters of the governor.