Kerry Taylor

The Citadel, Charleston SC

Many of us who have remained largely on the sidelines of the events surrounding the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri and Denzel Curnell in Charleston are hiding behind three comforting fictions. The first fiction relies on the presumed character flaws of the victims. In Curnell’s case we learned through leaks to the press of his alleged emotional instability, his spotty military record, and his theft of his stepfather’s gun.

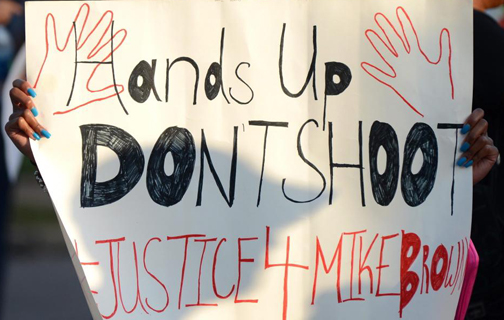

Assuming that the official version of his death is accurate and that Curnell committed suicide, that suicide took place after he was unnecessarily accosted by an off-duty police officer. It was the precipitating factor in Curnell’s death. In Ferguson, we learned from the police department that Brown stole cigars from a convenience store just minutes before the confrontation that ended in his death. Curnell’s and Brown’s alleged misdeeds, vulnerabilities, and reputations are nevertheless irrelevant. The US Constitution and Bill of Rights protect citizens from the undue use of state force, even those who look “like a demon,” as Michael Brown’s assailant described him to the grand jury.

A second justification for our silence and inactivity rests on the fiction that African-American leaders have been hypocritically indifferent to “black on black” crime and that they should spend more energies chastising African Americans, especially young people who do not conform to mainstream cultural norms. There are several problems with this line of reasoning. First, there is no such thing as black on black crime as a distinct social phenomenon. Statistically, African Americans murder one another at roughly the same rate as other ethnic groups.

While crime rates in some areas with large concentrations of non-white residents are unacceptably high, I would be hard-pressed to identify a civil rights leaders who has not devoted a tremendous amount of energy towards addressing issues related to crime and violence in its many forms. Locally, African American activists have worked tirelessly and often productively with law enforcement officials and church leaders to enhance crime fighting strategies.

Moreover, police violence is wholly different from violence perpetrated by one citizen against another. Through my taxes and votes, I sponsor and pay for state violence. Talk of black on black crime should be understood for what it is—a racist diversion from our shared responsibility to one another.

The final convenient fiction too many of us use to justify our silence is the notion that protests and riots are counterproductive and undermine the possibility of reform. Martin Luther King Jr. consistently denounced the urban revolts of the 1960s, arguing “that a riot merely intensifies the fears of the white community while relieving the guilt.” But King also recognized that “a riot is the language of the unheard.” It is a form of protest for those who have no access to conventional avenues for expressing dissent.

In the final months of his life, King sought to harness the energy of the urban rebellions and channel it towards pressuring the federal government to enact policies that would address poverty and economic inequality. King pledged that his Poor People’s Campaign would be “nonviolent, but militant, and as dramatic, as dislocative, as disruptive, as attention-getting as the riots without destroying property.” King did not live to realize that vision.

Those of us who profess to believe in fairness and peace need to move from behind the myths that have provided us with protective cover. Racial disparities in law enforcement are real and they demand our attention. In King’s words: “As long as justice is postponed we always stand on the verge of these darker nights of social disruption.”

Kerry Taylor teaches US History at The Citadel. He is co-editor of volumes four and five of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. and served as an editor at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project at Stanford University from 1997 to 2004.