Can the White House restrict the First Amendment based on political considerations? This will be the central question at a Federal Court hearing in Charleston, SC, at 10am on Oct. 27.

The hearing on a Writ of Coram Nobis, translated as “the error before us,” filed by Brett Bursey, will examine evidence suppressed at his trial in November 2003. A coram nobis petition applies to persons who have already been convicted and have served their sentence. Such motions cannot be used to address issues of law previously ruled upon by the court, but only to address errors of fact that were not known at trial or were knowingly withheld from judges and defendants by prosecutors that might have altered the verdict were they presented at trial. The writ argues that the government withheld evidence of White House involvement in segregating peaceful protestors from supporters of President Bush at presidential rallies. Bursey was arrested at a Bush rally in Columbia in October 2002 for refusing to be segregated from the general public.

Bursey, Director of the SC Progressive Network, is the only person ever convicted under a federal statute that allows the Secret Service to create a secure zone around presidential events. Bursey was arrested on state charges of trespass at an appearance of President Bush when he refused to go to an obscure “free speech zone” a half-mile away from the event. Four months after the arrest, state charges were found unconstitutional and dismissed. Federal charges were then brought by US Attorney Strom Thurmond Jr. under the statute that governs “Presidential Assassination, Kidnapping and Assault” (Title 18, United States Code, Section 1751(a)(1)(ii)).

“I argued at my trial that the Secret Service was being used as an armed political advance team by the president to keep protesters out of sight of the venue and the media,” Bursey said. He filed discovery motions and subpoenas during his trial for any White House directives to the Secret Service, but the government successfully moved to deny his efforts, calling them a “fishing expedition.”

Bursey has since discovered the White House Advance Manual that instructs the Secret Service to do what he alleged the agents had done. “There are several ways the advance person can prepare a site to minimize demonstrators,” the manual reads. “First, as always, work with the Secret Service and have them ask the local police department to designate a protest area where demonstrators can be placed, preferable not in view of the event site or the motorcade route” (pg. 32, Presidential Advance Manual).

Bursey was convicted of standing on the side of the road, 200 yards from the event, with a sign that read: No More Wars For Oil. His attorneys will argue that the White House and the Secret Service worked in concert with local police to deny the First Amendment rights of those opposed to the Bush Administration’s policies.

Bursey’s lead attorney, Michael Tigar, will be assisted by trial attorneys Lewis Pitts and Rauch Wise, Bursey’s trial counsel, and Columbia attorney Joyce Cheeks.

A member of the Duke University Law School faculty, Tigar is one of America’s leading constitutional lawyers. Justice William J. Brennan has written that Tigar’s “tireless striving for justice stretches his arms towards perfection.” In 1999, the California Attorneys for Criminal Justice held a ballot for “Lawyer of the Century.” Tigar was ranked third, behind Clarence Darrow and Thurgood Marshall.

Tigar is author or editor of more than a dozen books. He has also written three plays and dozens of law review articles. Tigar has represented The Washington Post, John Connally, Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, Scott McClellan, Rep. Ronald Dellums, Mobil Oil, Fernando Chavez, Lynne Stewart, Angela Davis and Terry Lynn Nichols. He has tried cases in many courts across the country, and argued seven cases in the U.S. Supreme Court, as well as dozens of federal appeals.

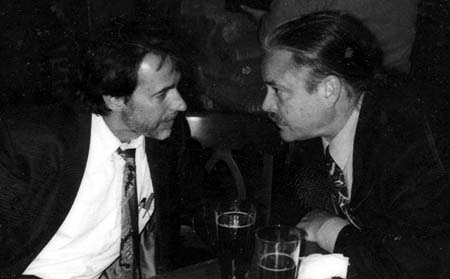

Attorney Lewis Pitts, left, and Brett Bursey.

•••••••

To hear an audio recording of Bursey’s statements during sentencing in 2003, click here.