To put our organizing work into context and better understand the legacy we’ve inherited, the SC Progressive Network will explore our ancestors’ radical roots at its 20th fall conference on Oct. 22 in Columbia.

Activists from across the state will meet at the Harbison campus of Midlands Tech for a Network membership meeting 10am – 2pm, to tend to internal business, hear updates from member groups about their projects, and look ahead to the upcoming legislative session.

In the afternoon, we invite the public to join us for a symposium with some of the state’s leading activists and historians. Led by University of South Carolina historian Dr. Bobby Donaldson and political scientist Dr. Sekou Franklin, the session will detail the vanguard role that Modjeska Monteith Simkins and South Carolina’s black activists played during the 1940s in the long struggle for civil rights.

After the Network’s meeting, we invite the public to join us for a symposium with some of the state’s leading activists and historians. All events will take place at the Harbison Campus of Midlands Tech.

The afternoon session – led by University of South Carolina historian Dr. Bobby Donaldson and political scientist Dr. Sekou Franklin – will detail the vanguard role that Modjeska Simkins and South Carolina’s black activists played during the 1940s in the long struggle for civil rights.

The meeting marks the 70th anniversary of the 1946 Southern Negro Youth Congress conference held at the Township in Columbia, a little-remembered but historic gathering. (See event program here.) Simkins did trainings at what was then Harbison Junior College for two dozen young blacks, mostly students, who spent 10 days studying black history, politics, civics, world affairs, and organizing techniques.

Simkins helped establish 11 chapters across the state that turned out over 400 members to the October 1946 weekend conference in Columbia. More than 2,500 people, from Birmingham to New York, filled the Township auditorium with the intention of striking a death blow to Jim Crow.

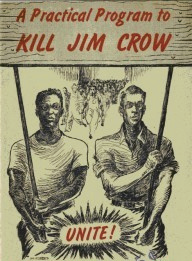

1945 Socialist Workers Party Pamphlet

1945 Socialist Workers Party Pamphlet

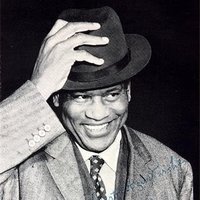

It was an impressive gathering. Julian Bond’s father came from Atlanta. Angela Davis’ mother came from Birmingham. The legendary Paul Robeson sang. Labor organizers and Communist Party members came from the north, and delegates came from as far away as Latin America and Africa. Our best notes on the conference come from FBI files that reported 170 participants were white, mostly union and peace activists.

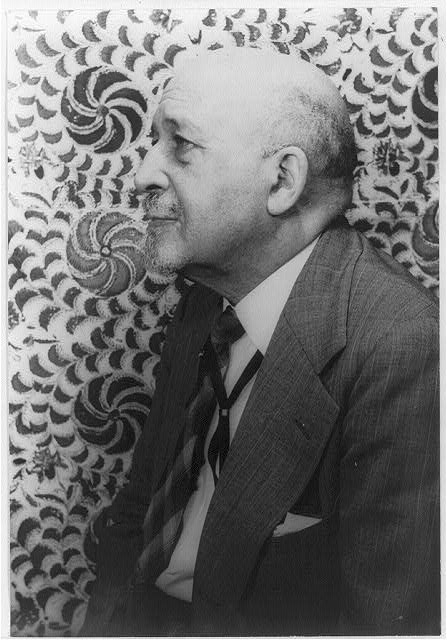

Dr. W.E.B. DuBois gave the keynote speech that Sunday at Benedict’s Antisdel Chapel. The speech, Behold the Land, lifted up as among the nation’s best, rings true today. DuBois called on “young women and young men… to lift the banner of humanity… in the midst of people who have yelled about democracy and never practiced it.”

DuBois rose to national prominence in 1905 with the founding of the Niagara Movement that challenged Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist positions on segregation. He was instrumental in the founding of the NAACP in 1909, and the National Negro Congress and the Southern Negro Youth Congress in 1937.

The Columbia SNYC conference was the largest human rights event the South had ever seen, with a class analysis of racism and a call for a mulitracial united front. By the time of the Columbia conference, black soldiers were returning from WWII to the hostile welcome of Jim Crow segregation. South Carolina was in the nation’s spotlight for having the last white-only primary, the South Carolina Progressive Democratic Party crashing the 1944 national Democratic convention (20 years before the Mississippi Democratic Freedom Party), and the blinding of Private Issac Woodard by police at the Batesburg bus station in February 1946.

Erik Gellman’s 2012 book Death Blow to Jim Crow claims that SNYC was more than a precursor to the modern civil rights movement; it was “the most militant interracial freedom movement since Reconstruction, one that sought to empower the American labor movement to make demands on industrialists, white supremacists and the state as never before.”

After WWII, white supremacists used anti-communism to beat back racial equality and labor organizing. We learned in our South Carolina high school history books that “carpet baggers and scalawags induced many of the ignorant and child-like Negroes to turn against the white people,” (Simms-Oliphant) and the Klan arose to beat back the 1870s Reconstruction and save the South.

Seventy years later, white supremacists like Gov. Jimmy Byrnes identified communists as the outsiders leading blacks astray. Simkins was “red-smeared up and down South Carolina,” and iced from the SC NAACP leadership in 1957 by black ministers who chaffed at her strong spirit and militant politics. The red scare effectively ended the militant era of civil rights, and domesticated the modern civil rights movement. That period is now recognized as one led by black ministers beginning in 1954.

DuBois called SNYC’s work the “second Reconstruction,” making the case that the gains of the first Reconstruction had been erased through the whitewashing of history. Now, ironically, 70 years after DuBois bemoaned the erasing of the first Reconstruction, we are studying the lost stories of the second Reconstruction of the 1940s – an astonishing period when the citizenry organized a serious challenge to the status quo – right here in South Carolina.

It is this under-valued people’s history that the Network is committed to lifting up, both at this conference and through its leadership institute the Modjeska Simkins School for Human Rights. While we’ve only recently discovered the importance of SNYC and Simkins’ deep involvement in that effort, the school is picking up where she left off, teaching similar solutions to sadly similar problems.