Legislature urged to make law agencies process data to see how prevalent it is

By John Monk

The State

The General Assembly needs to order all law enforcement agencies to process the racial data they collect on their traffic tickets to provide a snapshot of whether there is evidence of racial profiling.

That’s the conclusion of a 26-page report on racial profiling in state traffic stops just released by the S.C. Progressive Network. (You can download the study here.)

The state Highway Patrol analyzes the race of drivers given warning tickets by troopers because of a 2005 law. But it doesn’t analyze the race of those given actual citations for such offenses as driving under the influence of alcohol, speeding or breaking the state’s seat belt laws.

Other law enforcement agencies collect similar racial data on tickets of their own volition, but also don’t analyze it.

All of that needs to change, according to Brett Bursey, director of the S.C. Progressive Network.

“After all, the race of over 2 million drivers a year is already recorded on all traffic tickets, but that data is not put in a form so it may be examined for patterns,” Bursey said.

Racial profiling is a term that refers to the improper targeting of a motorist because of his or her race, not because of a driving issue.

Bursey said that since the General Assembly is required this session to review a 2005 state law that mandated that warning ticket data be analyzed, now is the time for that issue to be studied anew.

The 2005 law requires the Senate Transportation Committee and the House Education and Public Works Committee to make recommendations on how that law can be improved – if any are deemed necessary.

Rep. Joe Neal, D-Richland, a longtime supporter of better racial traffic stop data, agreed with Bursey.

“This goes to public confidence in laws and justice. To ensure our system is truly color blind, we need to understand what actually is happening when tickets are given,” Neal said.

Analyzing existing racial traffic stop data apparently would not be difficult or cost much money, law enforcement officials indicated.

Neal and Bursey say the state already collects and analyzes racial data in two law enforcement areas: prison populations and suspects arrested for serious crimes like murder.

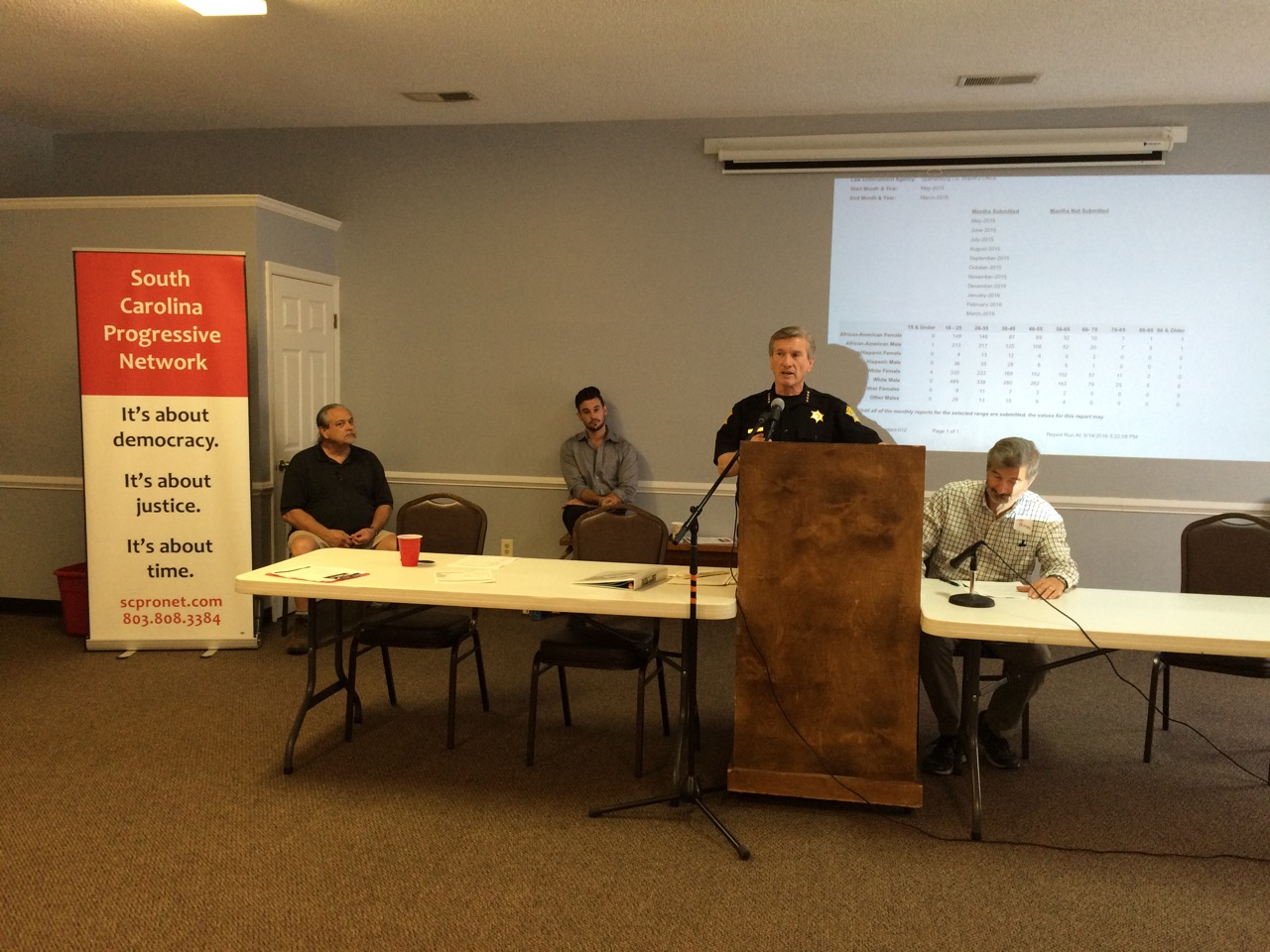

And one major agency – the Richland County Sheriff’s Department – has been collecting and analyzing racial data on its 20,000-plus annual traffic stops for 10 years.

“It’s fast and it doesn’t cost anything,” said Sheriff Leon Lott.

Lott’s data gives an overall picture of how the race and ethnicity of stopped motorists compares with county racial demographics. The individual traffic stop records of each of Lott’s 500 deputies can be easily examined for possible profiling, he said.

Three years ago, Lott said, his data helped prove a deputy was targeting blacks and Hispanics. The officer was arrested and fired.

Statistics alone aren’t proof of racial profiling, Lott said. Further investigation is needed to establish the complete situation, he said.

“The statistic is the baseline to start looking,” he said.

A spokeswoman for the S.C. Department of Motor Vehicles, which handled 1.9 million adjudicated traffic tickets last fiscal year, said it wouldn’t be difficult to write a software program to extract an overall racial picture of citations in which people have been found guilty of violations.

DMV official Beth Parks estimated it would take about two hours and cost at least $200 to arrive at a computer-generated racial profile of last year’s citations to which people were found guilty. She did not have an estimate of what percentage of the 1.9 million citations itwould be.

Last year, as the 2005 law required, the DPS analyzed – and made public – overall race data on 377,676 warning tickets the Highway Patrol issued.

But those warning tickets are only 41 percent of 904,348 tickets it issued last year for seat belt, DUI and other violations.

Last week, DPS director Mark Keel, at The State’s request, examined how his agency handles racial data in the 59 percent of actual citations.

“We have learned we do have the ability to do things with this data that we have not fully explored and fully utilized,” Keel said.

For example, said Keel, DPS can access each trooper’s record of the race of the people who get citations. Racial breakdowns of all citations in individual counties also are available, Keel said.

In the past, such matters as reducing the highway death rate and dealing with budget concerns, have taken much of his attention, Keel said.

But DPS already is having conversations about how to make better use of the data, including possibly making some of the overall patterns publicly available, Keel said.

Keel also said troopers’ supervisors already monitor their officers’ performance, and any racial profiling should be detected now, from an examination of troopers’ tickets issued as well as video made at traffic stops. Before Keel assumed his job in 2008, a few of those videos made the news because they showed troopers mistreating motorists, some of them black.

An official at the Denver-based National Conference of State Legislatures, which tracks state laws, said a “fair number” of states track and process racial profiling data for traffic stops. She did not have specific numbers.

Lott said he has had good results gathering such data.

“It’s another tool,” Lott said. “You do it because it’s the right thing to do.”

Bursey said he hopes law enforcement will take the lead on creating a transparent database. “Good cops don’t mind sharing this data with the public.”

(The Progressive Network’s report can be viewed at www.scpronet.com.)